(ZENIT News / Rome, 07.30.2025).- In the world of Catholic religious life, few names evoke as much admiration and reverence as that of Pedro Arrupe. The Spanish Jesuit who led the Society of Jesus from 1965 to 1983 was seen as a spiritual giant—intellectually brilliant, deeply prayerful, and compassionately committed, particularly remembered for his care of atomic bomb victims in Hiroshima. His legacy inspired countless young men to join the Jesuits, and in 2019 the Church officially opened his cause for canonization.

But new revelations emerging from a civil case in Louisiana are forcing the Church to confront a more complicated picture of Arrupe’s leadership. At the center of the controversy is Donald Barkley Dickerson, a former Jesuit priest whose name now appears on the Society’s public list of credibly accused sexual abusers. The legal documents reveal that as early as 1977, Arrupe was made aware—by one of his top provincial leaders—that Dickerson had been accused of sexual misconduct with minors.

And yet, Dickerson was eventually ordained.

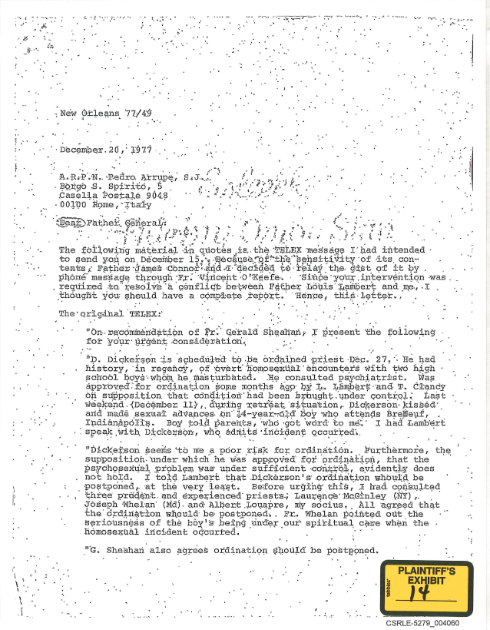

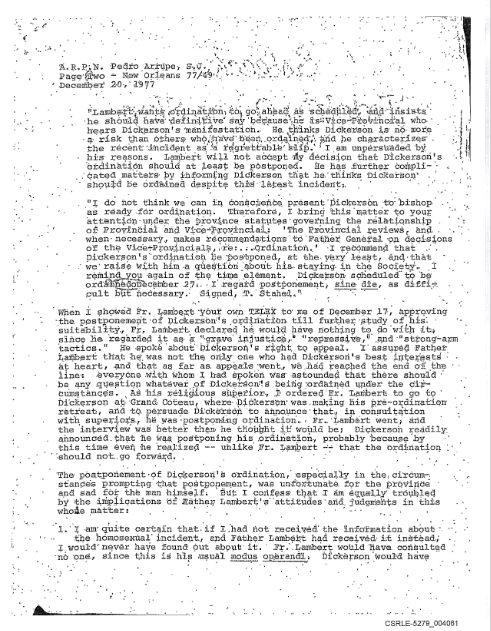

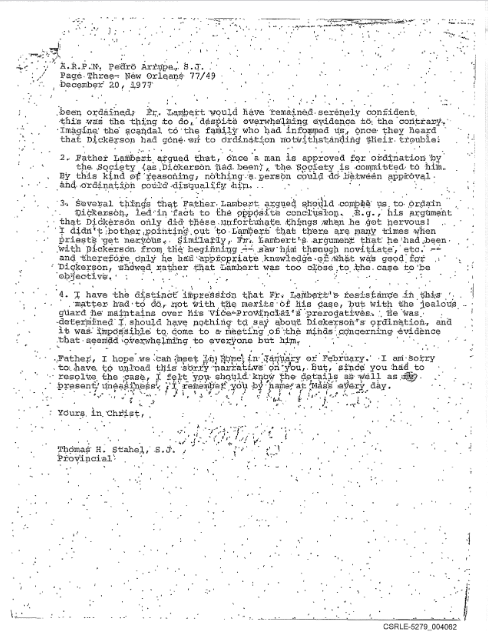

The warning came in a letter sent directly to Arrupe by Fr. Thomas Stahel, the then-provincial overseeing Jesuit communities in the southern United States. Stahel wrote that Dickerson had a troubling history, including prior sexual behavior with two high school boys, and more recently, had made inappropriate advances toward a 14-year-old during a retreat. Stahel was unequivocal: “I do not believe we can, in conscience, present Dickerson as ready for ordination.”

The letter—found among archival records now submitted in court—forms part of a broader legal action filed in June 2024 by a man who alleges that Dickerson raped him in 1984 while he was a 17-year-old freshman at Loyola University New Orleans, a Jesuit institution. The case has renewed difficult questions about how Arrupe, a man so often celebrated for his moral courage, handled warnings about abusive clergy under his watch.

It also raises sobering concerns about the processes within religious orders at the time. Instead of referring the case to civil authorities, the Jesuits sent Dickerson for psychiatric treatment and later proceeded—despite multiple documented accusations—with his ordination. Internal letters reveal that Dickerson was described as struggling with inappropriate behavior when “under stress,” and that those close to him believed he was trying to change. The judgment to delay, but not cancel, his ordination reflected a dangerous pattern of misplaced trust and quiet hope in rehabilitation—patterns the Church now publicly admits were grave mistakes.

In the years that followed, Dickerson continued to serve in schools and parishes. He was eventually removed from the Jesuit order after a series of additional allegations surfaced in 1986. By then, at least seven credible reports had been made. More would come later. The man who filed suit in 2024 said Dickerson invited him into community meals with priests, grooming him under the pretense of pastoral care before initiating abuse that, according to the suit, escalated to rape.

The case not only implicates institutional failures at multiple levels, but forces a reckoning with how the Church remembers its revered leaders. Arrupe’s involvement may have been limited to correspondence, and the surviving documentation does not indicate whether he approved the ordination against advice or simply deferred to others. But his name is now inextricably linked to a decision that had lasting consequences for victims.

In a deposition this June, Fr. John Armstrong—a Jesuit who once worked near Dickerson—admitted that the handling of the case was deeply flawed. “It was horrible that it was handled that way,” he said under oath. “I feel terrible for the victims. I don’t understand how, after the first incident, he was allowed to continue.”

The revelations come at a time when Pope Leo XIV has reiterated the Church’s zero-tolerance stance on abuse, warning bishops and religious leaders not only against sexual exploitation but against the broader abuse of power, conscience, and trust. In his address to the Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors in June, he emphasized that credibility is built not on words, but on transparent action.

It is precisely this credibility that is now under pressure. While Arrupe’s canonization cause continues—driven by admiration for his prophetic vision and spiritual depth—his handling of Dickerson’s case introduces painful questions. Can holiness and administrative failure coexist in a candidate for sainthood? Can a leader’s silence or inaction—whether due to lack of clarity, trust in others, or the institutional culture of his time—undermine his sanctity?

The Catholic Church has made significant reforms over the last two decades. Bishops and superiors are now required to report credible accusations to authorities. Safeguarding training is mandatory in most dioceses. Still, these changes cannot rewrite the past. They can only make its lessons clear.

For many victims, healing begins with truth—not only about the abusers, but about those who allowed them to persist. Pedro Arrupe’s legacy will always carry the light of Hiroshima, where he stood beside the wounded. But now, in a courtroom in Louisiana, his name appears beside a different kind of suffering—one born not of war, but of betrayal. The Church must now decide how to reconcile both.

Thank you for reading our content. If you would like to receive ZENIT’s daily e-mail news, you can subscribe for free through this link.