(ZENIT News / Rome, 08.03.2025).- Over the course of the last decade, something historically significant has taken place across the globe: the gradual erosion of Christian majorities in countries that once seemed inseparably linked to the faith. From the cathedrals of Europe to the chapels of Oceania, Christianity—while still dominant in many regions—is quietly losing ground, according to a recent report by the Pew Research Center.

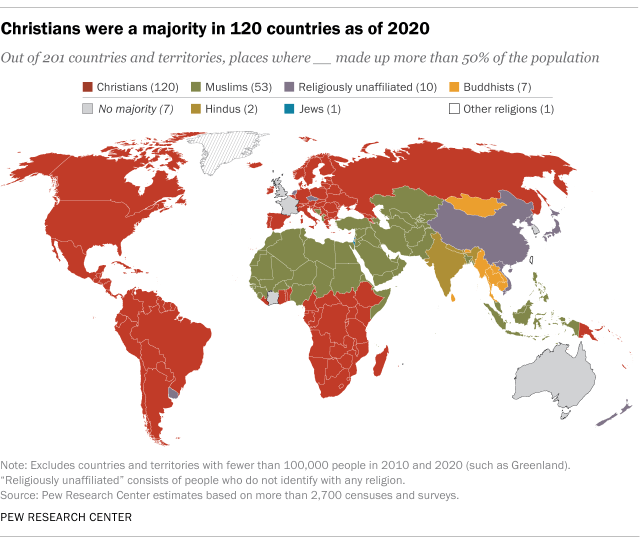

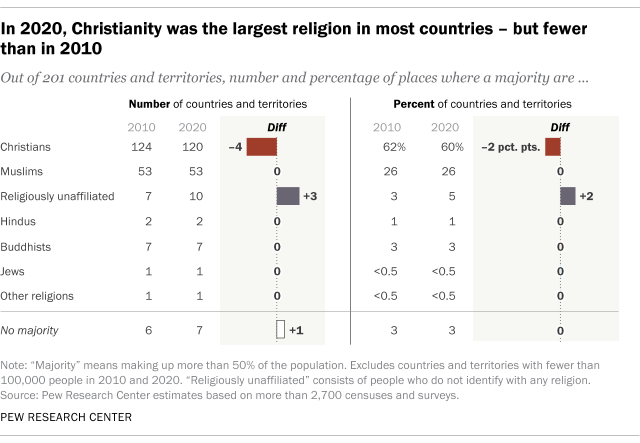

As of 2020, Christians remained the majority in 120 of the 201 countries and territories surveyed. That figure still accounts for 60 percent of all nations—but it marks a noticeable drop from 2010, when 124 countries had Christian majorities. The trend reflects a broader shift in religious identification, with millions leaving Christianity behind—not necessarily for another faith, but often for none at all.

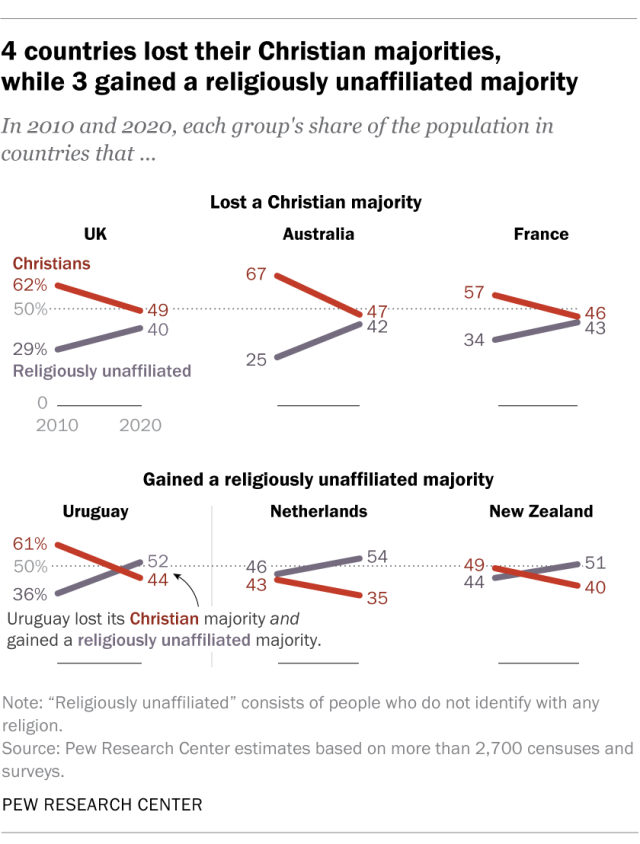

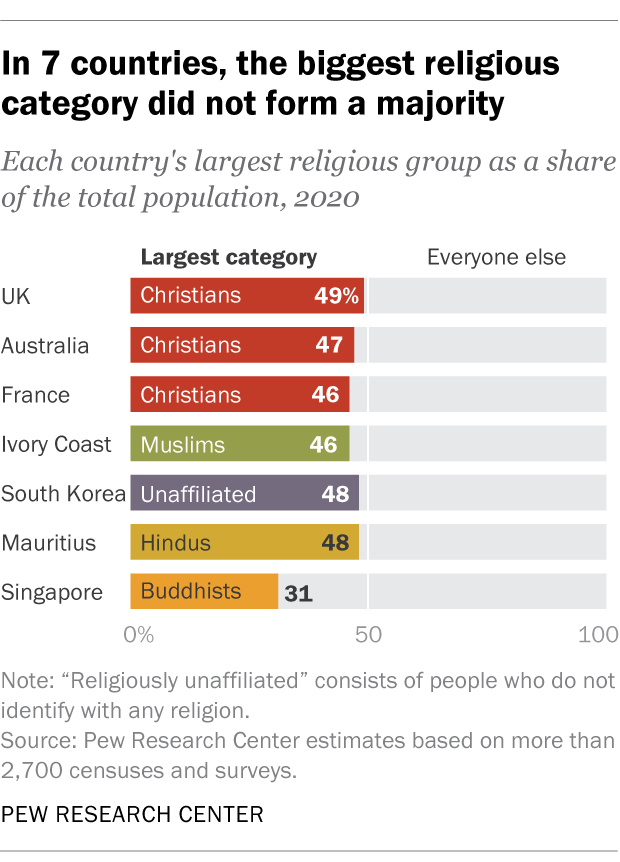

The losses are particularly pronounced in nations long associated with Christian heritage. Between 2010 and 2020, four countries—France, Australia, the United Kingdom, and Uruguay—slipped below the 50 percent threshold of Christian self-identification. In the UK, Christians represented just 49 percent of the population in 2020. In France, it was 46 percent. Australia stood at 47 percent, and in Uruguay, the number had dropped to 44 percent.

Uruguay’s case is especially striking. Once shaped by a strong Catholic presence, it became in 2020 the only country in the Americas where a majority of the population—52 percent—claimed no religious affiliation at all. This category of the “unaffiliated” includes atheists, agnostics, and those who simply identify with nothing in particular. While their rise has been most visible in Western societies, it is also a global phenomenon.

Across the same decade, three countries joined the list of nations with religiously unaffiliated majorities: Uruguay, the Netherlands (54 percent), and New Zealand (51 percent). They followed the path of countries like China, Japan, and the Czech Republic, where religion has long played a limited public role. In total, 10 countries had unaffiliated majorities in 2020, compared to just 7 in 2010.

What emerges from the data is a portrait of a world where religion, particularly Christianity, is no longer the social default in many developed countries. It is not so much that other religions are replacing Christianity, but rather that a growing number of people are opting out of religious identity altogether.

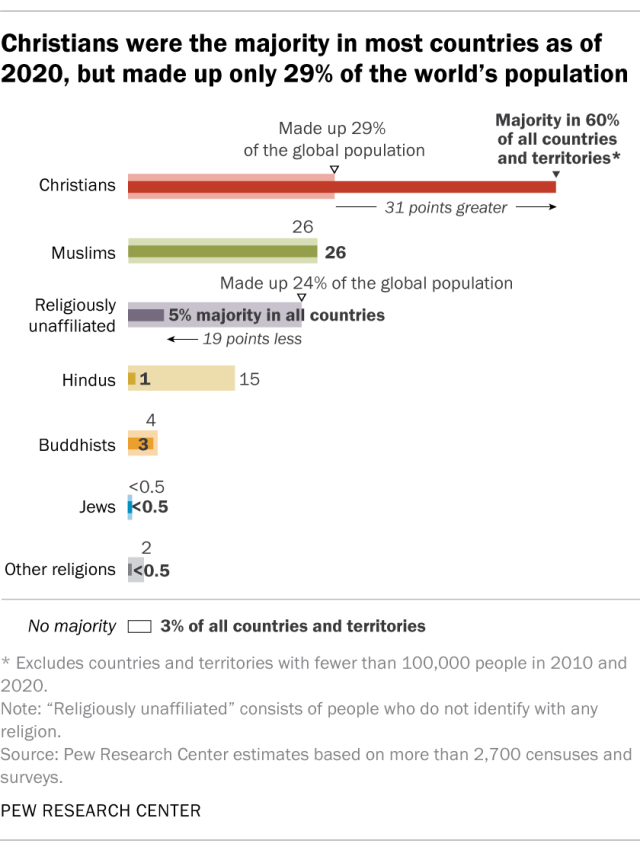

Still, geography and demographics reveal an uneven story. Despite losing ground in parts of Europe and the Americas, Christians remained strikingly widespread. While they made up only 29 percent of the global population in 2020, they formed majorities in 60 percent of countries surveyed. This is largely because Christianity spans regions with vastly different population sizes—from microstates like Micronesia to powerhouses like the United States.

In contrast, some of the world’s largest religious groups are more geographically concentrated. For instance, Hindus represented 15 percent of the global population in 2020, but only formed the majority in two countries: India and Nepal. Islam, representing a comparable global share, had majorities in 53 countries—the same number as a decade earlier. Buddhists, too, remained a majority in just seven nations. Meanwhile, Jews and adherents of other faiths held the majority in only one country each.

The shifting religious map does not necessarily suggest the end of religion, but it does challenge long-held assumptions about its cultural permanence. In some countries, the departure from Christianity has left no clear replacement—no new dominant belief, only a growing silence where religious affiliation once spoke for most.

For the Catholic Church and other Christian traditions, the implications are complex. On one hand, the loss of majority status in traditionally Christian nations might prompt a fresh evangelizing spirit—one that no longer takes cultural Christianity for granted. On the other, it raises urgent questions about secularization, generational change, and the credibility of religious institutions in postmodern societies.

Christianity has survived declines before—often to be revived in surprising ways and places. But this moment is different in its scale and pace. The trend, though not universal, is undeniable: Christianity is no longer the cultural baseline in parts of the world where it once defined not only personal faith but national identity. What fills the vacuum remains to be seen.

Thank you for reading our content. If you would like to receive ZENIT’s daily e-mail news, you can subscribe for free through this link.